The average annual earnings for a doctor in the United States is $350,000. That's 50% more than physicians are making in Germany.

Part of this difference is explicable in terms of differences in wage rates between countries. On average, Americans earn significantly more than Germans. But that explanation is insufficient to cover the full delta.

Another part of this difference is explained by the simple fact that America pays its doctors a pretty remarkably high amount by global standards; a Medscape survey found even more profound differences between the US and other rich nations. While a European doctor might be comfortably in the top 10% of the income distribution, an American doctor, on average, is comfortably in the top 3%.

One might think these uniquely high wages in the United States would lead to a disproportionately high percentage of the American population seeking a career as a doctor. But that understandable assumption would be wrong.

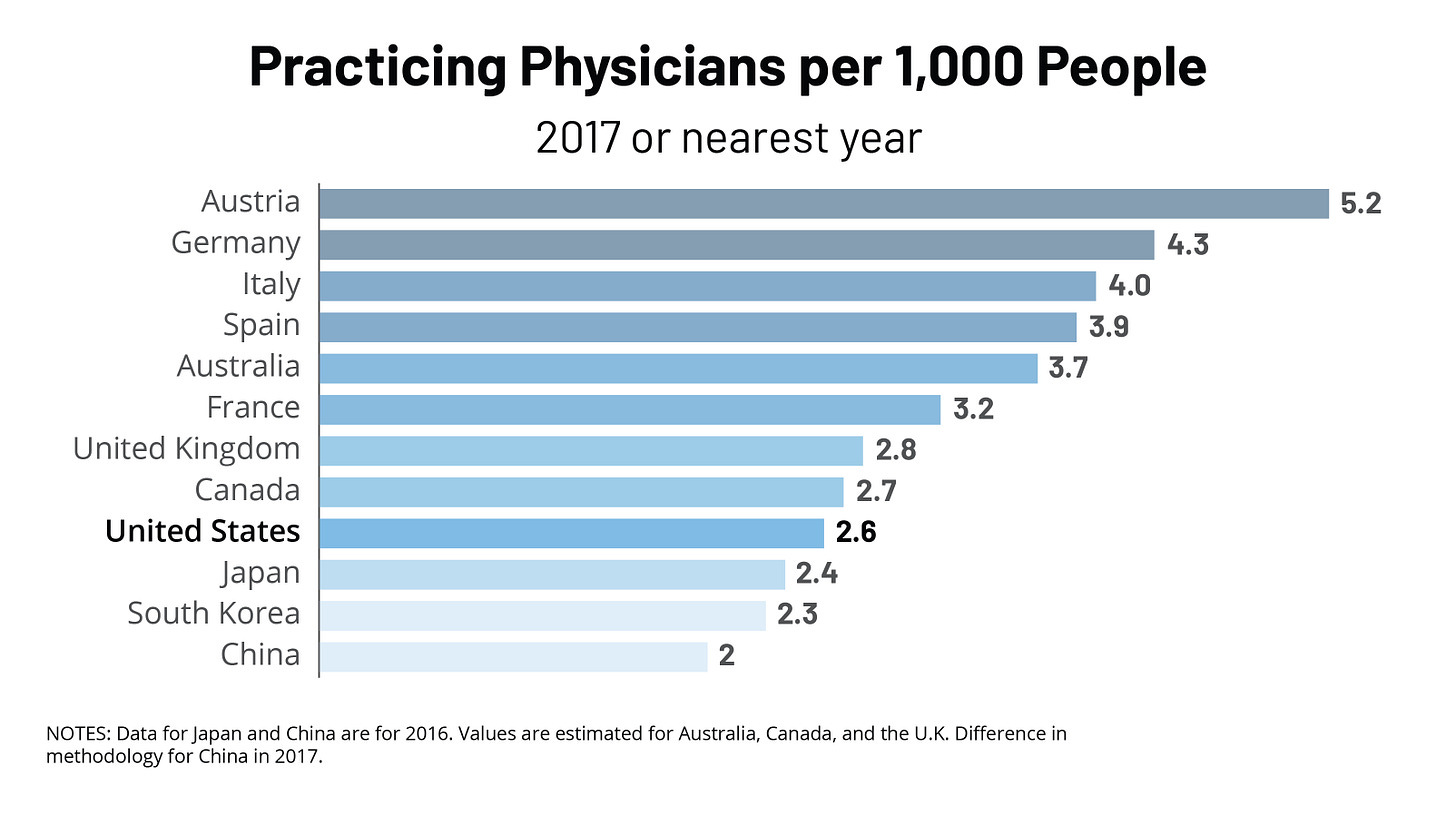

Despite lower relative wages, Germany has 65% more physicians than the United States does per capita. This statistic is one of many that sheds light on an issue at the heart of America’s healthcare woes.

The United States has, by international standards, a uniquely low number of physicians per capita. While some peer nations may be able to get away with this due to exceptionally healthy populations, our population, plagued with chronic illness, certainly does not.

The present supply of physicians is far out of lockstep with the demand for them, and high wages are a symptom of this. When the supply of anything fails to be fully elastic in the long run, its price tends to go up (lest demand, for some reason, fails to grow over time). Similarly, as the supply of doctors has been limited, the price of doctors (their wages) has grown.

Mechanically, this is caused by the competition between insurers. As time with a doctor is increasingly scarce, insurers competing against one another effectively bid up the price. American consumers end up paying higher taxes to fund increasing government spending on healthcare programs and higher premiums for their own insurance.

Another symptom is long wait times. Americans wait far longer to see a physician than people in almost any other advanced nation. When they do, they see their doctor for a shorter time, with visits lasting, on average, only about 20 minutes.

Patients suffer the consequences. The shorter the length of a visit, the higher the likelihood the doctor prescribes an inappropriate treatment for their condition. The human cost of this is borne out in the data. A large 2023 cross-sectional study found that “shorter visits were associated with a higher likelihood of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for patients with upper respiratory tract infections and co-prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines for patients with painful conditions.”

The good news is that the physician shortage is something that can be fixed, but in order to do so, we need to first understand how it has come about.

Part 1: It’s too hard to become a doctor

Becoming a doctor in the United States is one of the most difficult career paths a person can follow.

Students, starting in high school, need to study hard to get good grades; they also need to get a decent score on their SAT or ACT so they can get into a good college.

Then, they need to complete a four-year undergraduate program and must continue to get excellent grades while also completing pre-medical school requirements.

After that, they must get an excellent score on the MCAT (in the 75 percentile or above), which often requires many months of intensive study.

Following this step, they will enroll in a medical school program, which will take them on a four-year process of intensive training. Over the course of these four years, they will take multiple state licensure exams, which require passage in order to eventually legally practice.

Following graduation from medical school, they will need to apply for a residency. If they are accepted, they will be under years of painstakingly difficult training with low compensation.

At the tail end of this process, prospective doctors will be confronted with a final third licensure test, the hardest of the bunch.

Over the course of this, at a minimum, 11-year process the median student will accrue $215,000 dollars in student debt.

Gap years or longer residencies for specific specializations will stretch it across yet even more years. The numerous points of potential failure will, through attrition, pick off many of the people pursuing this career path, ultimately preventing them from entering the workforce as physicians.

All of this contributes to the doctor shortage. The more barriers, whether they be in difficulty, financial costs, or time dedication put up to becoming a doctor. The fewer people who will be willing to pursue that path, the fewer people who will end up on the other side. Furthermore, the longer the period aspiring doctors are locked up in the education system, the shorter their time as practicing physicians will be.

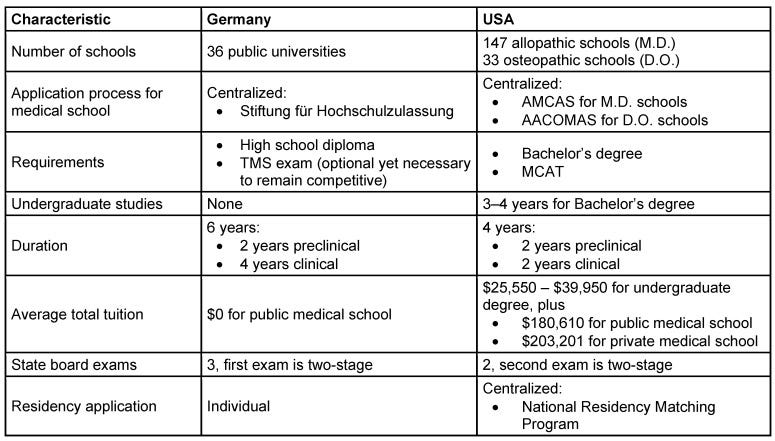

Other countries that are graced with a far more abundant supply of doctors have a much less strenuous process by comparison, without much, if any, evidence that their medical professionals are of notably lower quality. Let’s look specifically at Germany’s process since I referenced them previously.

As shown in the image above, pulled from an insightful comparison of the German and American approaches to training physicians, the German system is notably less arduous than the American system.

Upon graduating high school, students are permitted to go directly to medical school. High grades are sufficient to secure acceptance, although optional entrance exams are available for those with lower grades who seek to prove their abilities.

The duration of medical school is one to two years longer, but it is tuition-free. The state licensure exams are incorporated into the medical school system and do not include additional exams after one has graduated, and once graduating, a residency is virtually guaranteed by a national matching program, without the requirement for stressful and tedious applications.

Part 2: There aren’t enough medical school seats or residencies

Another part of the cause of this problem is that there aren’t nearly enough medical school seats or residency positions.

To demonstrate this visually, consider the above graph. The blue line represents the total number of new first-time medical school applicants, and the orange line represents the total number of medical school students accepted. As you can see, the two are increasingly out of lockstep, which manifests in falling acceptance rates at medical schools.

Despite the difficulty of becoming a physician in America, there are still a lot of people who want to do so. Attracted by high levels of compensation, tens of thousands of Americans try and fail each year to get into medical school.

Many of these applicants are high quality. They have the talent, knowledge, and work ethic needed to succeed in medical school and have GPAs and test scores that would have gotten them into medical school a decade ago when admissions requirements were lower. However, because of an insufficient supply of seats, their applications get chunked.

For those lucky enough to get into medical school and graduate, one estimate finds that 7% fail to secure a residency spot afterward, leaving them unable to continue their path toward becoming a physician and also flailing in debt.

So, what’s causing this preposterous lack of seats? One would think that in a market, if the demand for medical school seats and residency spots grew, and the applicants for these positions were sufficient in quality to meet state licensure standards, the supply would increase accordingly. This would predict that, in the long run, applicants and training program positions would increase in lockstep.

The issue is that our physician education process isn’t a marketplace. Most medical school seats are at public universities. The remaining are in predominantly nonprofit universities. Regulations exist that limit expanding seats at medical schools, and new schools are required to go through federal accreditation with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education, which can be challenging.

Most residencies are funded through a complex formula by Medicare, and the supply of residency slots is controlled by residency review committees staffed with professionals from the specialty in question.

Expectedly, the system doesn’t act very much like a market because market forces are hard to find. This, of course, leads to problems.

Part 3: Bureaucrats and special interest groups are to blame

Many of the groups involved in these state-controlled processes have an incentive to limit supply. A notable group that has caught substantial flack for this in the past is the American Medical Association, which advocates for the interests of doctors. Current doctors financially benefit from limiting entrance into their profession, as this allows them to extract artificially high wages. This phenomenon gives special interest groups like the American Medical Association an incentive to limit supply, and that is an incentive that has historically acted in accordance with.

In the late 20th century, it was these poorly incentivized interest groups and some poorly informed bureaucrats that produced the widespread myth of an impending “doctor shortage.”

A major catalyst for this alarm began in 1976 when the secretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare commissioned the Graduate Medical Education National Advisory Committee to provide policy recommendations on the healthcare workforce. This report, released in 1981, alleged that the U.S. needed to take immediate action to constrain the supply of doctors.

The American Medical Association and related professional organizations were eager to push this narrative. In 1997, they issued a joint statement asserting that “the United States is on the verge of a serious oversupply of physicians.”

Over the course of these years, serious action was indeed been taken to limit the supply of doctors. Federal funding for scholarships was cut. Residency requirements were intentionally made more stringent to reduce the quantity hospitals provided. The number of Medicare-funded residency slots was frozen.

A moratorium on new schools was declared, leading to almost no new medical schools being opened from 1980 to 2005. Class sizes also shrunk, and planned expansions of existing medical schools were canceled.

Along with the newly created artificial limits on supply, additional laws were crafted to artificially increase the demand for physicians. Scope of practice restrictions were imposed in states across the country to exclude nurses and other trained professionals from providing many forms of care, thereby increasing the need for doctors.

Today, the narrative has shifted. The Association of American Medical Colleges has rung alarm bells regarding a projected shortfall of up to 86,000 physicians by 2036. Even the American Medical Association has come around to recognizing the sorry state of doctor supply. Although, predictably, their “solutions” consist primarily of more subsidies, not supply-side expansions.

However, as the discourse on the topic has changed, many of the policies that caused it have remained in place. Occupational licensing requirements are too strict, and the education process is too arduous and long. Scope of practice laws prevent other medical professionals from doing things they can safely do, unnecessarily reducing competition and increasing the need for physicians.

Government funding for expanding medical school seats has been insufficient. Private nonprofits have also failed to grow their schools at a sufficiently quick rate. Private for-profit schools, which theoretically could fill gaps in the public and nonprofit supply of seats, are heavily regulated.

A challenging federal accreditation process required by state regulatory boards prevents new schools from opening, and expansions of existing programs similarly face challenging government hurdles.

The residency process continues to rely on an incredibly complex federal funding system that supports a number of residency spots that are mostly unchanged from what they were decades prior. Furthermore, their supply is controlled by largely unaccountable entities that lack the incentive to approve an adequate number of positions.

Part 4: Deregulation, restructuring, and supply-side investments can fix it

The solution in the face of the present system, plagued by centralized control and special interest group rent-seeking, is a healthy dose of deregulation, restructuring, and supply-side investments.

That includes policies like:

Reforming medical school by removing bachelor’s requirements for medical school admissions, increasing the length of medical school programs to cover any necessary learning lost from undergraduate pre-med courses, and investing in research to find the most cost-effective and fastest ways to prepare people to practice.

Revising the occupational licensure process by eliminating unnecessary requirements and embedding it entirely into the medical school system.

Lowering the upfront cost of attendance by supporting financial instruments like income share agreements, which allow students to go to school debt-free in exchange for a certain percentage of their income over a number of years.

Changing the scope of practice laws so that nurse practitioners and other medical professionals can perform the full range of services they can safely provide.

Making it easier to start new accredited medical schools and expand existing ones, and making public capital available for that purpose.

Eliminating all caps on residency slots and restructuring Medicare residency funding to provide a fixed subsidy amount for every spot that meets federal standards.

Establishing a unified residency sorting process that ensures all medical school graduates can easily and quickly secure a residency.

These reforms would allow more people to get jobs in the lucrative medical profession. They would bring down healthcare costs and allow Americans to see their doctors faster and for longer periods of time.

Furthermore, they would make the aspiration of universal, affordable access to care a lot more practicable. Currently, the fact that many people don’t have insurance or have insurance makes the effect of the physician shortage on wait times less extreme than it would be otherwise.

An unfortunate and often under-recognized fact about our current healthcare system is that if universal, affordable access to care were achieved tomorrow, the consequence would not be everyone getting the healthcare they need when they need it. Rather, it would be everyone having the right to wait in line to see a doctor, and a long line at that.

Better than the status quo? Yes.

Ideal? No.

With these reforms, we would make the full aspirations of universal high-quality healthcare for all possible. And make our society wealthier and healthier in the process.

Excellent overview. Agree with all the sugges posed except one. Students should complete a Bachelor's degree before going to med school. Many students going into medicine especially in US need this time to mature emotionally and educationally which will make them better doctors. There are great differences in the European and US public schools system. German students may be more ready to study the indepth content necessary for medicine than American counterparts. But the rest of the steps would be a welcome change.

When you die because your doctor provided subpar treatment I will laugh at you and point to this article