For as long as society has been imperfect, there have been attempts to discern why.

Why is it so many are impoverished in a world of such plenty?

Why do governments so often act against the interest of the people?

Why is the environment continually degraded despite our knowledge of the negative consequences of doing so?

These are some of the questions we can so frequently ask ourselves, and through a wide variety of methods, many come to one answer: Class

Class, in the view of many, is the central fixture of history, the lens through which nearly all contradictions make sense. The evils of Feudalism are explained by the class interests of the lords and how they clashed with those of the serfs. A similar story persists in Mercantilism and again in modern Capitalism.

At the end of the day, the separation of those who own and those who toil is of central importance. And this separation, when channeled through nation-state apparatus, also can be made to explain the inequality between nations and the domination of western capital over the national capital of the global south.

Even the defenses of Capitalism (along with previous class societies), and the collection of ideologies that justify it’s hierarchies can be made more comprehensible with class analysis.

Maybe the proponents of Capitalism are but an expression of class ideology. Liberalism, Conservatism, and Libertarians alike might be but different channels of the propaganda of the ruling class infecting the public minds and convincing them to justify their own servitude, tighten their own shackles, and bow their heads further to their oppressors.

The class meta-narrative of evil is surely appealing, but the unfortunate fact is despite its elegant simplicity and historical grandeur, it crumbles when thrown against the world as it actually exists.

1 It’s a distributional problem

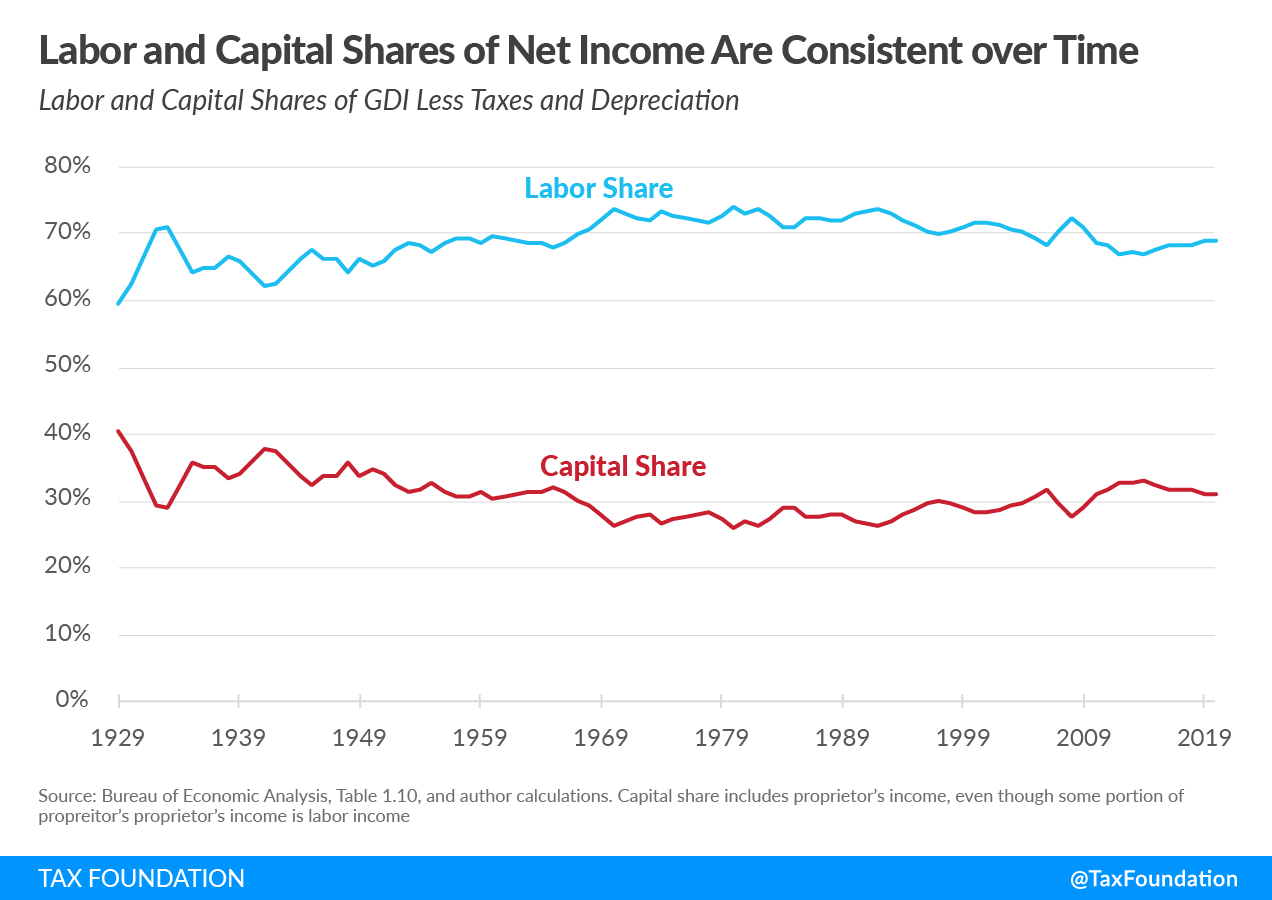

Common among those with a class oriented view of our problems is the rejection of the fixation on scarcity. Possibly despite the insistence of the rulers and their mouthpieces, development is of secondary importance. “Growth” concerns could be just a distraction from redistributing the massive sum we already have.

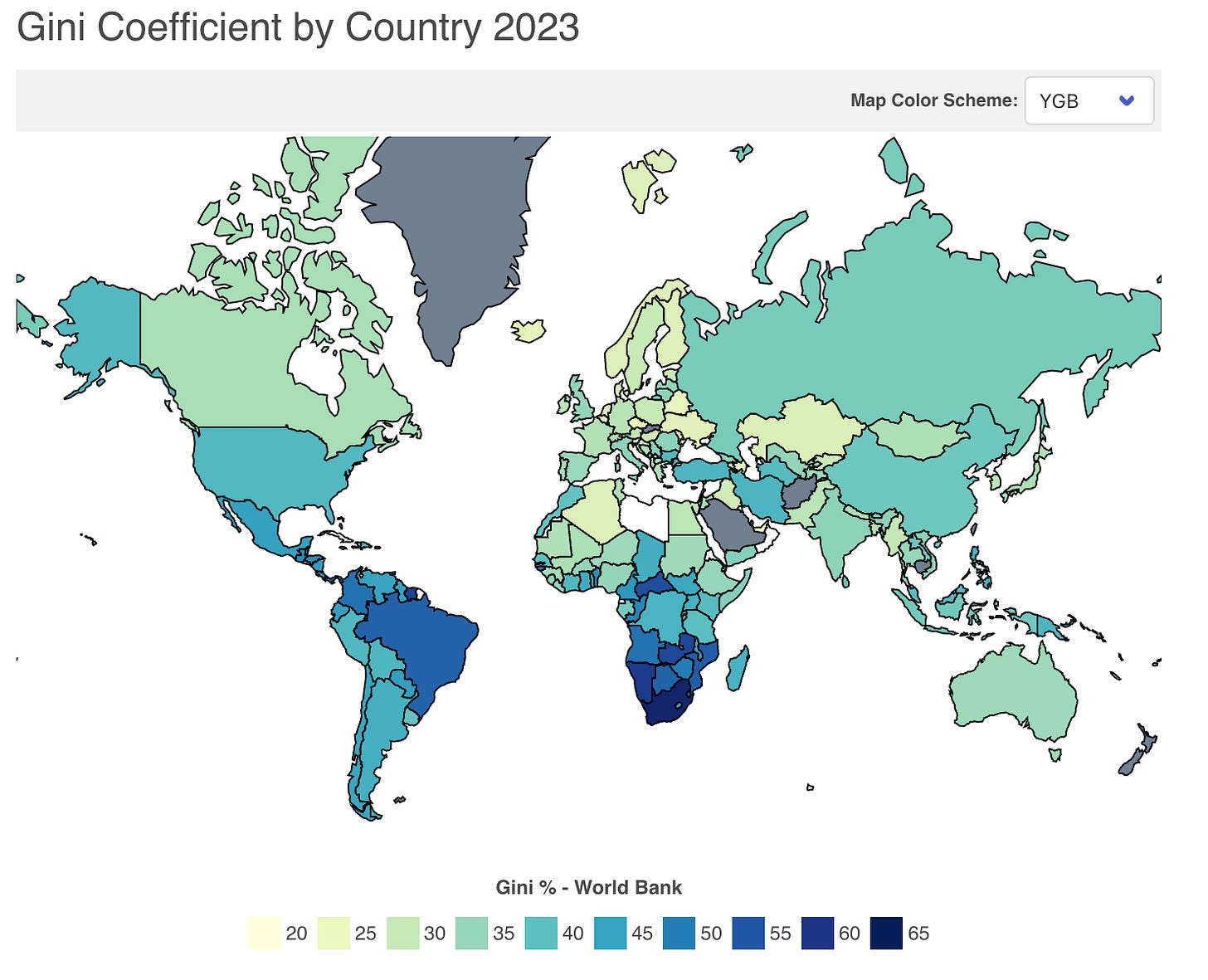

Yet, for such a view, the math simply doesn’t add up. The world is not impoverished simply or even primarily because of exploitation; it is because we are poor.

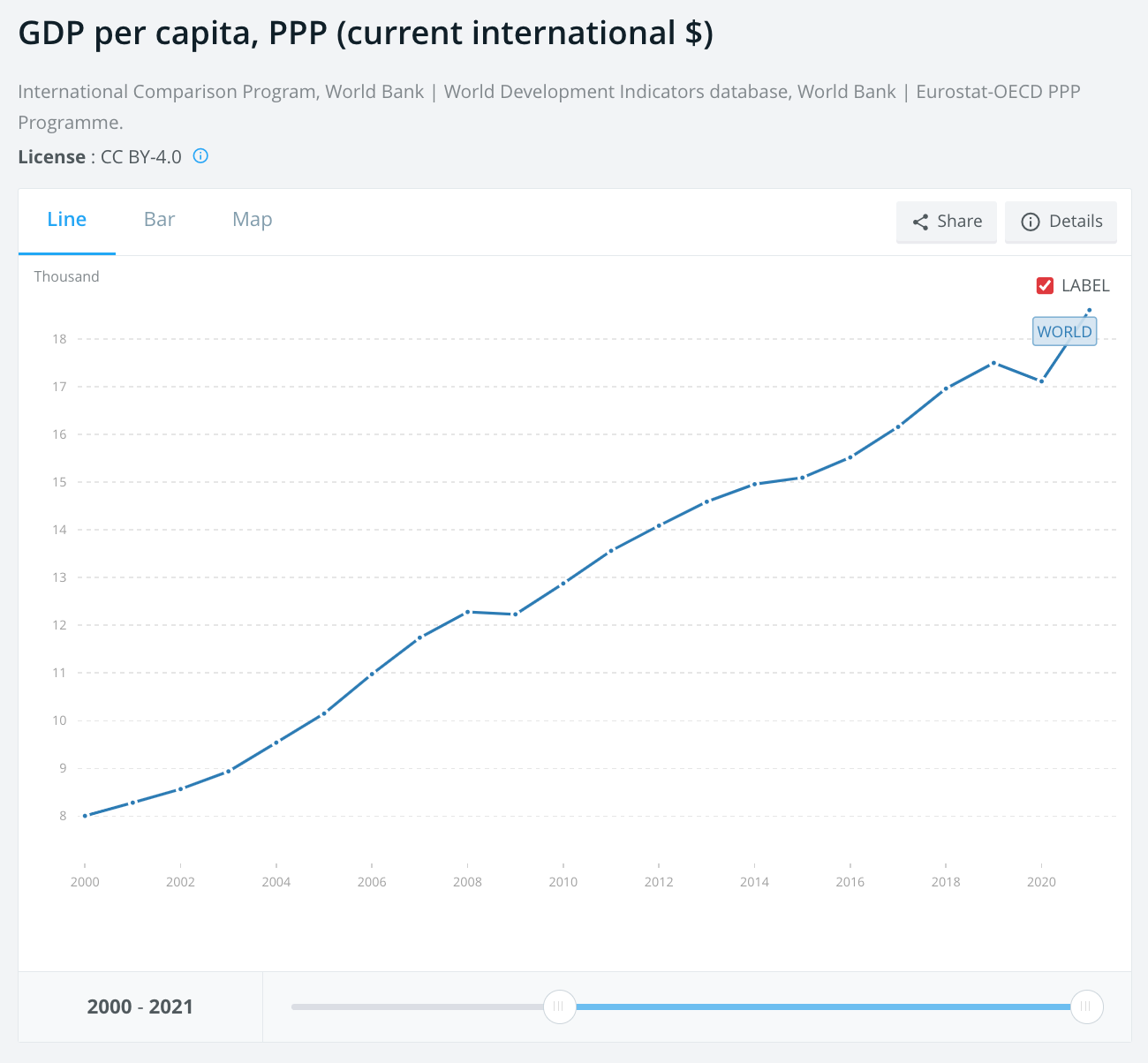

Even if the entirety of global economic output were divided evenly among every person, we would only have 18,603 dollars per person if these dollars were adjusted to the purchasing power of the United States. This isn't that far above the poverty line of 13,788.

Of course, despite how paltry of a sum this is, even it is massively exaggerating the level of equality that could be achieved. A large sum of money must be taken out for essential public services like public safety, courts, emergency services, etc.

Perfect equality is not possible. People who work harder and longer must get paid more to be incentivized to do so. For, if there was absolutely no material gain for working, we can expect an extremely sharp reduction in output (if not a total economic collapse), which would mean we would have even less to go around than we already have.

Furthermore, full equality between nations (or the geographic areas they embody) is unfeasible, even in a world where we have one global government. The uneven distribution of capital guarantees this remains, to an extent, the case.

Redistributing the pie from haves to have-nots is entirely insufficient for satisfying everyone on this earth with a standard of living above poverty, let alone a good one.

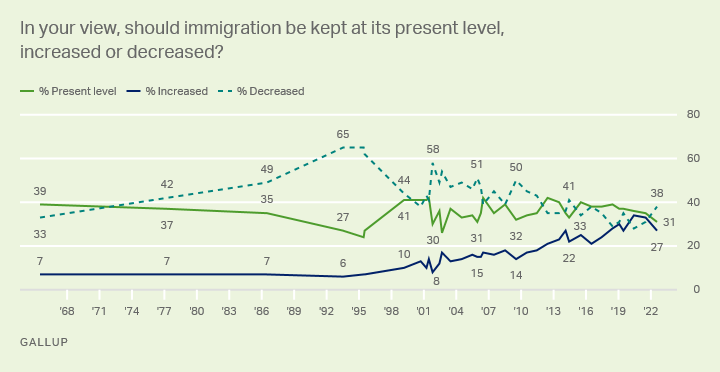

To the extent that redistribution is something we should do, the most radically redistributive policy any nation could conceivably engage in is allowing free immigration from the nations of the global south. This would hugely increase their income and also help grow global output.

But what is the biggest barrier to this becoming a reality? Not capitalists, not the financial elite, but voters and workers.

Voters, many of them with reactionary sentiments, don't find the idea of members of the global poor living among them particularly appealing, and workers find it against their interest to expand the scope of competition for employment (surprisingly, though, they are incorrect in this assessment). If both groups ceased holding these views, the barrier to free immigration would be eliminated, and we would quickly see a huge reduction in poverty and inequality as measured globally.

Current levels of national inequality can and should be reduced, but enhancing global growth and reducing international inequality are far more important priorities.

2 The government is a tool of the rich

It’s commonly said, “the system is working, just not for you.” The implication of the ominous statement is that the government is working for some “them,” and in the case of those principally concerned with class, that means the rich. Yet, this is clearly not the case in Western democracies.

American policy deviates extremely wildly from what is in the interest of the rich. Why would the rich support certificate of need laws and huge entrance barriers to becoming a doctor when doing so increase the cost of doing business substantially?

It’s because they don’t; CON laws are the product of ignorant policymakers and the American Medical Association, an organization that serves the interest of doctors.

Why would the rich want the United States to have 80+ welfare programs that all have extremely high waste and often provide substantial disincentives (because of welfare cliffs) to work? They don’t; this mess of policies is only sustained because of poor political institutions and the ignorance of politicians.

Why would the ruling class support restrictive zoning and expansive building regulations, which massively reduce their capacity to engage in profitable development? Once again, it's not them!

NIMBYism is the product of the interests of a concentrated local homeowner class more than anything else. An interest that directly contradicts that of the aggregate interest of capitalists yet is the leading driver of growth in inequality over time.

Furthermore, the impact of corporate intervention in policymaking is often exaggerated.

A study by professors Stephen G Bronars and John R. Lott looked to see whether there was any identifiable impact of changes in PAC contributions and voting behavior. They also studied how politicians voted in their retiring term (where PAC contributions were no longer relevant) and compared that to how they voted previously in their careers. The results were clear; there was no observable impact. In the words of the authors:

“Our tests strongly reject the notion that campaign contributions buy politicians votes”

Another study, this time by John Matsusaka of the University of South California, found that politicians vote with the majority of their constituents approximately 65% of the time. Crucially, though, no connection between campaign contributions and divergent behavior was identifiable. In his words:

“The evidence is most consistent with the assumption of the citizen-candidate model that legislators vote their own preferences.”

A much bigger deal than contributions appears to be lobbying. A study by professor Amy McKay found that Lobbying intensity does, in fact, have a significant impact on policy, but the intensity is not directly related to the amount of spending.

These studies tell a very distinct tale from the one we often hear. Politicians are not bought; their genuine point of view is influenced. Donations are made to support politicians who already support a given position, not in order to change their minds. Lobbying success is not directly determined by the amount of money invested but rather by the persistence of the lobbying firms’ efforts to sway legislators to their side.

In the end, politicians usually vote with the majority of their constituents. When they don't, they usually do so because they think differently, whether that be because of their own contemplation or because their mind has been changed by lobbyists.

Corporations among other groups (labor and issue groups) can influence outcomes, but when they do so, they generally get policies that benefit specifically them, usually to the detriment of the rest of society, including the Capitalist class.

3 Capitalists hate green things

Climate change is a problem that endangers the well-being of us all and specifically those in the global south, but class explanations work no better here than anywhere else.

Societies where Capitalism is not present have been just as bad at environmental custodianship as capitalists. The Soviet Union was notorious for its environmental track record. Toxic waste was frequently dumped in bodies of water. Due to this practice, nearly all the fish in the Oka River were dead by 1965. Mass irrigation projects siphoned enormous amounts of water from the Aral and Caspian seas, devastating local ecosystems.

"The attitude that nature is there to be exploited by man is the very essence of the Soviet production ethic."

- Economist Marshall Goldman

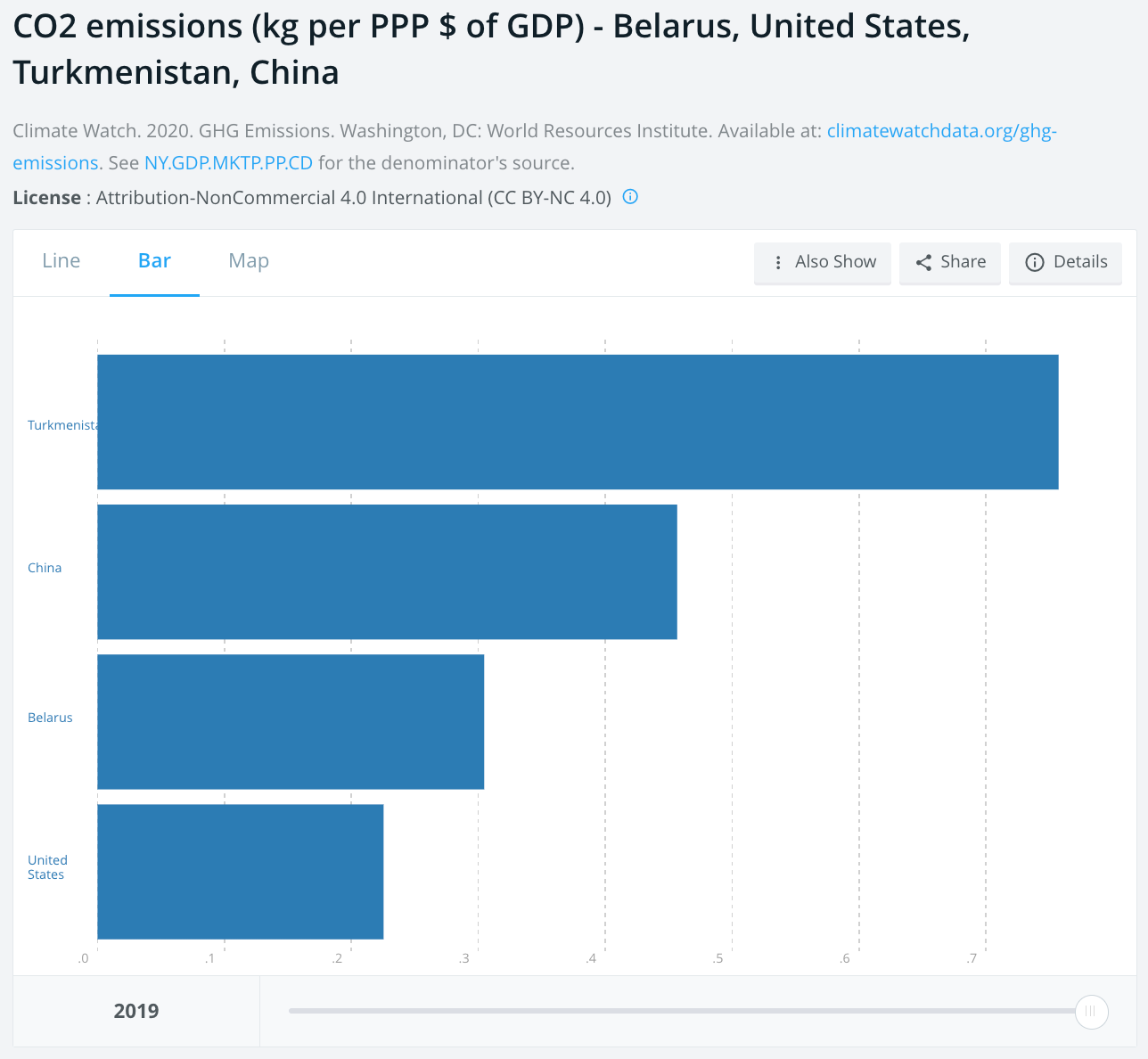

Belarus and Turkmenistan, two places where the state is the dominant economic driver, are some of the worst when it comes to sustainability and pollution. Surprisingly, even in the United States, the poor track record of the state regarding the environment holds true, with researchers finding that Government entities were more likely to violate the U.S. Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act than private firms.

It is true that Capitalism struggles with externalities, but this is also true of all systems. A Market Socialist society would still give worker-owned enterprises a direct financial incentive to pollute when doing so is more profitable.

In State-Planned Societies, the incentive remains. So long as those who manage enterprises are not the physical embodiment of the interest of all persons (an impossible feat without advanced AI), economic decisions will remain imperfect.

Capitalism is not uniquely culpable for climate change. A destroyed world is a world with less profit; the ruling class also loses in that world and loses big time.

The only companies pushing against change are those that are invested in fossil fuels and unsustainable practices, but their interest and the interest of their workers contradict that of everyone else! For every billionaire funding the fight to keep fossil fuels around, there is another throwing obscene amounts at some environmentalist organization.

The world’s problems are far too complex to be explained by the owning class vs the people. We live in a world of billions of individuals who exist within many different groups. Because of imperfect institutions, these groups often find their interest to be in conflict with that of the interests of the public.

Whether these groups are by industry, religion, ideology, or nationality, this misalignment produces problems. Often, the government fails to adequately realign incentives because they themselves are under the undue influence of special interest groups.

On top of this is the ever-present factor of ignorance. Not only do many interests contradict the well-being of the whole, but also individuals are frequently imperfect thinkers. They misidentify problems and the solutions to those problems. Class obsession is one of these misidentifications.

Eating the rich won’t satisfy our appetite; in fact, it will only leave us more hungry. Fixation on reducing our complex problems to class obscures our ability to identify the genuine, nuanced reasons things are actually dysfunctional, which all too frequently do not involve simplistic class dynamics.

While it is pleasurable to think there is a silver bullet that can rid the world of its problems, and all it takes is to end the tyranny of some evil minority. Reality is much more sobering. To make a better world, we must try to align everyone’s incentives as much as possible with that of the whole, cure ourselves of our ever-present ignorance, and try to confront in the best possible way the inherent scarcity that constrains us.

Another world is indeed possible, but we must abandon populist reductivism to realize it.

Great article. I feel like your average Twitter leftist would be so much happier just learning more about economics and backing solid policy. Most of them seem to be leftists not because they cracked open Das Kapital and liked it, but because someone online told them they wouldn't have to work anymore.

Strange also that leftists are unwilling to embrace data driven economics. Wouldn't a solid economics background inform their moral stances better? Isn't the best communist the one who can best articulate the policy decisions that bring them to their desired state of being? Aren't they always on about how evidence based their takes are? Why do they reject the very concept of data?

Even more confusing is when leftists reject the idea of democracy because "democracy doesn't work" when socialism is quite literally meant to be economic democracy. Combine these contradictions with the foggy proto-sociological assertion that "all history is class warfare" and data oriented people like me just have no clue what to even do with them. They're like flat earthers of economic policy.

Cool as always.