Means Testing is an Inefficient Tax

Pesky accounting tricks that make us poorer

A common point of conflict within the discourse surrounding social spending is how these social spending programs ought to be organized. Evidently, social spending is essential to ridding ourselves of the evils of poverty and ensuring that the gains of economic growth are distributed equitably.

But once this premise is accepted, the question remains, how?

Within the essential "how" question, there are many sub-divisions, like whether social transfers should come in the form of in-kind benefits or cash, whether they should be connected to work or not, etc. This article will avoid such entanglements to address one subdivision, means testing vs. universality.

The argument for means testing goes as follows:

While it is necessary for the state to devote resources to the purpose of social welfare, these resources should be exclusively used to create benefits and programs that target the needy. This ensures that programs are cost-effective and do not squander money on providing transfers to those who are already well off.

An intuitive line of thinking, no doubt, but one that collapses upon further inspection. While it is true that means testing reduces the cost of programs, this is more an accounting trick than anything else. To elucidate this point, take the following thought experiment (shamelessly stolen from Harvard economist Greg Mankiw)

Consider two basic income proposals:

A Universal Income is provided to all citizens of 10,000 dollars a year, financed by a 20% flat tax on all income.

A Negative Income Tax is targeted at citizens with 0 income, where they are provided 10,000 dollars annually. This income is then phased out at a rate of 20 cents for every dollar they earn. And then, once it fully phases out (once they earn 50,000 dollars or more), there is a flat tax on all income of 20%.

At first glance, there may appear to be a difference between the two programs. The first features an entirely flat benefit and flat tax structure. The second features a progressive benefit targeted at the poor and a defacto progressive tax targeted at only those earning more than 50,000 dollars a year.

Yet, in substance, there is no difference but administration. Everyone is left with the same amount of money in the first program as they are in the second. A 20% flat tax on the first 50,000 dollars is hardly different than phasing out a benefit at 20 cents per dollar of earnings.

Both reduce the real gain of earning a dollar to 80 cents. The only distinction is how they go about doing this. Proposal 1 does this explicitly by taxing income. Proposal 2 does this implicitly by tapering benefits.

Both have the same distributional impact, and if people were perfectly rational, the same impact on incentives. After all, 20 cents of each dollar is 20 cents, whether it comes out of your paycheck or out of your welfare check.

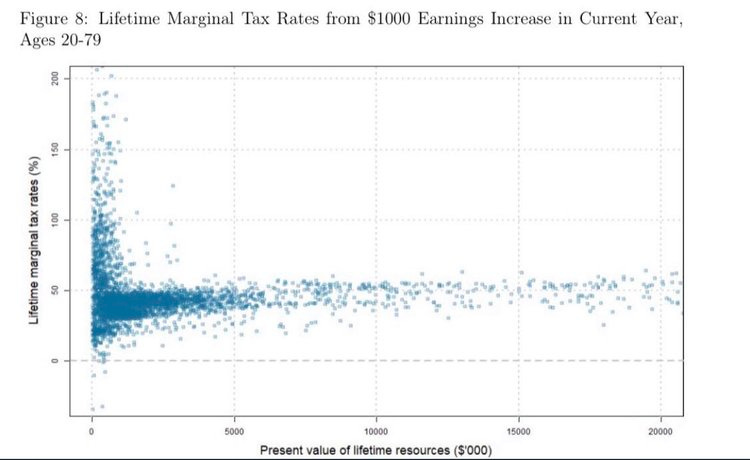

In other words, means testing acts precisely like an income tax. While means-testing may save money on paper, in terms of its actual effect on people's willingness to work, it should impact the economy just as negatively as a universal program of equivalent specifications would.

It is for this reason that talking about programs in terms of their price tag is fallacious. A universal program could cost on paper far more than a means-tested one while subjecting the population to lower effective marginal tax rates (phase-out rates + normal tax rates). At the end of the day, what matters is not how much money the government is taking in and sending out; it's about how government policy affects our incentives.

Now that we have established that means testing is a tax, let us get to the other aspect of this article's title, how it's inefficient. See, while in purely theoretical terms, the two aforementioned proposals may be equivalent, there are practical reasons to favor the former over the latter. Furthermore, when we analyze areas where benefits are targeted towards persons of a specific demographic, such as the disabled or parents, additional problems with means testing arise.

1. Means testing raises administrative costs.

If we were to have a program that gave poor people 10,000 dollars a year, we would probably want that 10,000 to be paid out over a distributed period of time. This serves a dual purpose; first, it eliminates the risk that all of it is impulsively squandered in a short period of time, and second, it gets people money when they need it. Since the eligibility for the transfer is based on yearly income, the only way to structure a bulk one-time transfer would be to require an impoverished person to wait until the end of the year to receive it, which would leave them in a state of destitution for an intolerable length of time.

Given this, we may desire to provide benefits on a monthly or biweekly basis. Yet doing would significantly complicate the administration of the program. Now the government would not only have to check your income at tax time, but also it would routinely have to determine an estimation of your yearly income in order to ensure that not only is it cutting you checks when you need them but also that these checks are the precisely correct size.

This increases the cost of programs, reducing the amount of money that actually gets to those in need.

2. Means testing allows the poorest to slip through the cracks.

Because predicting yearly income for the entire population is impossible, means-tested programs rely on applications. These forms can be found online or at government institutions and require those who believe they are eligible to report their income (and, in some instances, provide documentation) that the government then validates.

Unfortunately, many people never apply! A fact demonstrated ad nauseoum by current welfare programs. In 2020, 7 million people eligible for Medicaid and/or the Child Health Insurance Program did not enroll. A similar story is true for the Earned Income Tax Credit (which can be claimed upon filing federal income taxes) where the IRS estimates about 7 billion dollars go unclaimed annually. Universal programs avoid this issue by providing transfers automatically to all citizens/residents.

3. Means testing lacks the intra-annual income smoothing effect.

Under universal programs, one has a steady base material standard of living they can rely on on a month-to-month basis. In our thought experiment, everyone, no matter how rich or poor, can make decisions with the knowledge that 833 dollars will come in every month. This is beneficial whenever abrupt and unexpected changes happen in their financial situation.

Means-tested programs have no such feature; if a person who has already made 50,000 dollars for the year loses their job suddenly and is without income, they can expect to see no help from the basic income program.

This occurs despite the fact that they may have no or little savings. Currently, unemployment insurance acts to soften the blow of being laid off, yet universal programs ensure a greater degree of income smoothing on top of this effect, and unlike UI, they also help people who encounter financial turbulence from non employment-related sources (an unexpected medical bill, for instance) >

4. Means testing may suffer from "loss aversion."

20 cents is 20 cents, no matter where it comes from. Or is it? A number of behavioral studies have actually found that humans have an irrational bias toward minimizing perceived loss, even in equivalent situations. One study conducted by Silvia Aram of the University of Essex found that…

“Results indicate that participants who were exposed to a benefit withdrawal frame were more likely to stop working early compared to participants experiencing a direct tax frame…. This pattern suggests that loss aversion may play a role in shaping behavioural responses to social and fiscal policy.”

While this impulse may not be rational, if we do believe it is real, it would indicate that means testing has a greater disincentive effect than taxation.

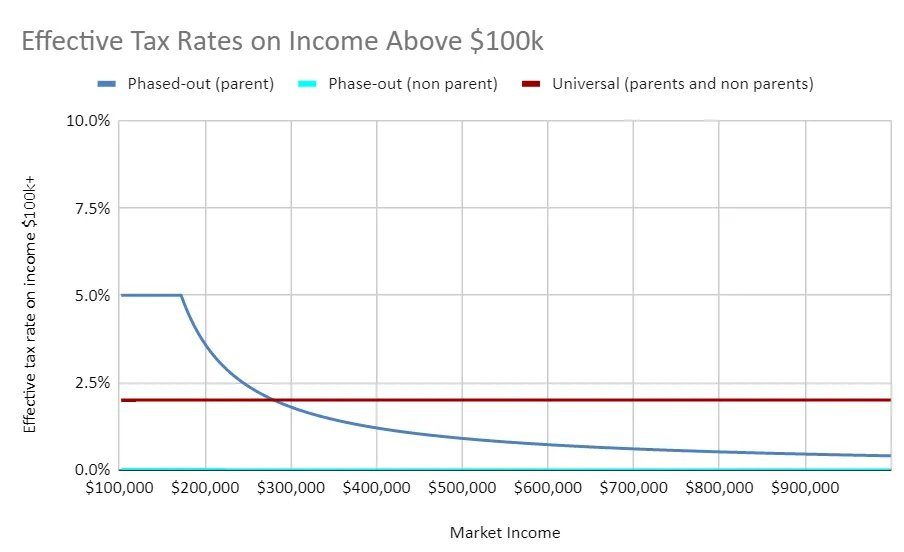

5. Means testing leads to inequities when subgroups of the population are targeted.

There are certain subgroups that society may want to help based on characteristics other than income level. For example, governments may want to bolster the income of parents to help ease the financial burden of having children or provide extra benefits for the disabled. They may also want to establish certain financial incentives for people to acquire electric vehicles or get childcare services.

The idea is that people that meet some sort of criteria should receive more financial support from the state than those who don't. Means testing makes this only true for those with incomes low enough to qualify and not true for everyone else. So while we may think a middle-class couple with five children should be treated preferentially to a couple of the same income with no children, means testing leads to both being treated precisely the same.

Recent Electric Vehicle tax credits passed under the Inflation Reduction Act exemplify this inequitable characteristic. Under the policy, individuals making under 150k are entitled to receive up to a 7500 dollar credit from the government if they purchase an electric vehicle (that meets certain requirements). Meanwhile, those over that threshold receive no such incentive.

This makes little sense. If the purpose is to incentivize people to purchase Electric Vehicles, it should apply even to the rich, and the additional cost of providing them with this incentive can be easily offset by a minor tweak to their tax rate.

Ultimately it is for all these reasons that means testing is an inefficient tax. It is more administratively costly, lets many poor people slip through the cracks, does not smooth income, suffers from loss aversion, and is inequitable. We should make no mistake that it, in no instance, is preferable to universality.

While it may be necessary as an element of proposals due to the ignorance of journalists and politicians alike and how heavily ingrained the price tag fallacy is into the public psyche, we should only accept it begrudgingly with the knowledge that it is, in every way, sub-optimal.

I referenced your article in mine about UBI vs negative income tax. I found that if the system is funded with sales or income tax, negative income tax is about 10 times more efficient (less deadweight loss) than UBI. But if funded by a tax that doesn't have deadweight losses (like land value tax) then UBI beats negative income tax: https://governology.substack.com/p/ubi-vs-negative-income-tax