Cashflow Taxation and It's Radical Implications

A weird intersection between Socialism and Neoliberalism

Economists specifically of the Neoclassical variety, are often accused of being shills for the elite. Their pleas for deregulation, liberalized labor markets, freer trade, and a tax policy that focuses less on capital and more on externalities and consumption are easy to view as a product of bourgeois propaganda. As a fixture within a machine whose sole purpose is to churn out propaganda that justifies the present social order and the inequalities therein.

But occasionally, they come up with an idea so shockingly radical, so revolutionary in its implications, that these assertions are made demonstrably false. Cash flow taxation is one of these ideas.

The thought process behind cash flow taxation is as follows. If the government wants to take a stake in the gains of an enterprise, it also must share the burden of investment in said enterprise and the losses of the said enterprise. For to only claim a portion of the reward without assuming any of the risk or expense would diminish the level of investment and, thus, growth.

This is what makes a tax on cash flow superior to that on capital gains or wealth. In the same way, it acts to reduce inequality and raise revenue for the government, but it does so without distorting incentives in a fashion that encourages people to consume more today and invest less.

It’s an idea that shares much in common with socialist notions of an economy where investment primarily comes from competing state institutions. Social Wealth Fund Socialists, or as they frequently describe themselves, “Liberal Socialists,” share an appreciation for the market with their neoclassical comrades but have come to the conclusion that leaving capital allocation in the hands of private actors yields excessive inequalities. They think that since most of the rich hire professional investors to manage their capital, there is nothing stopping the state from doing the same and, in the process, slowly eliminating the owning class and amassing increasingly massive sums of revenue that can be used for social purposes.

The issue, of course, is that there is a high likelihood the government would concentrate all the assets in too few funds (leading to an investment system more akin to economic planning); these investment funds would then have the herculean task of appointing the leadership for a huge number of companies and then meticulously monitoring them. Each of these funds itself would also require the correct institutional design, accountability measures, and monitoring by legislators to ensure it acts properly. And, if, at any time, the government decides to start using its authority over firm management to get them to pursue “social objectives,” a devolution into economic planning is inevitable.

It’s a highly risky wager. And for those of us that are more skeptical of the state, handing them direct control of the massive majority of firms feels, well, like a recipe for catastrophe.

The beauty of cash flow taxes is their capacity to capture much of the promises of Social Wealth Fund Socialism without the inevitable pitfalls such a system would most likely find itself falling into.

In practice, this means the government subsidizes all of a business’s expenses, and in exchange, by the same rate, it taxes its revenue. In the end, it breaks even when they break even, losses money when they lose money and makes money when they make money.

To properly showcase how this would work, let us imagine a donut shop:

A donut shop has a 100,000 of revenue and expenses of 120,000, so 100,000 - 120,000 = -20,000 in profit. Meaning that this year, the government will apply its cashflow tax rate, say 50%, to this -20,000. This leaves us with a balance of -10,000, meaning the government will pay the shop 10,000 dollars this tax year.

Suppose the company does better the following year with a revenue of 200,000 and expenses of 120,000. Well, then the government would apply its tax rate to the 80,000 dollar profit and receive 40,000 dollars for themself.

The crucial fact is that profits at the macroeconomic level are far greater than losses. This is why rich investors get richer over time as a group and don’t just spend each year wrestling over a fixed pot of gold.

Under this system, the government never picks any winners or losers and never exercises any decision-making power over firms. All the policy does is bet on everyone and then share in the rewards and losses with everyone. And as the literature on index funds has consistently shown, betting on the entire market on average generates higher returns than even most professional investors can garner!

Now that the case for cash flow taxation has been made, we can consider more difficult questions around implementation. We can look at some of the most common concerns here in a Q&A.

1. How do we minimize avoidance?

A common feature of corporate income taxes (the closest albeit far less likable sibling of cashflow taxes) is their high levels of avoidance. Under the current regime, corporations like Apple and Amazon nearly zeroed out their tax rate, using a whole host of clever tricks.

The chief culprit for this routine robbery of the treasury is attempting to make business taxes origin-based taxes. The thinking goes like this, American companies should pay taxes on their global income. So it doesn't matter whether the company is making money off sales here or in Morocco; they need to pay up.

The issue is that the origin of these profits isn't very easy to determine. Supply chains are global, and companies take advantage of this fact by engaging in profit shifting, whereby they transfer their profits to foreign subsidiaries in lower-tax countries disguised as payments for some form of good or service (usually leasing intellectual property).

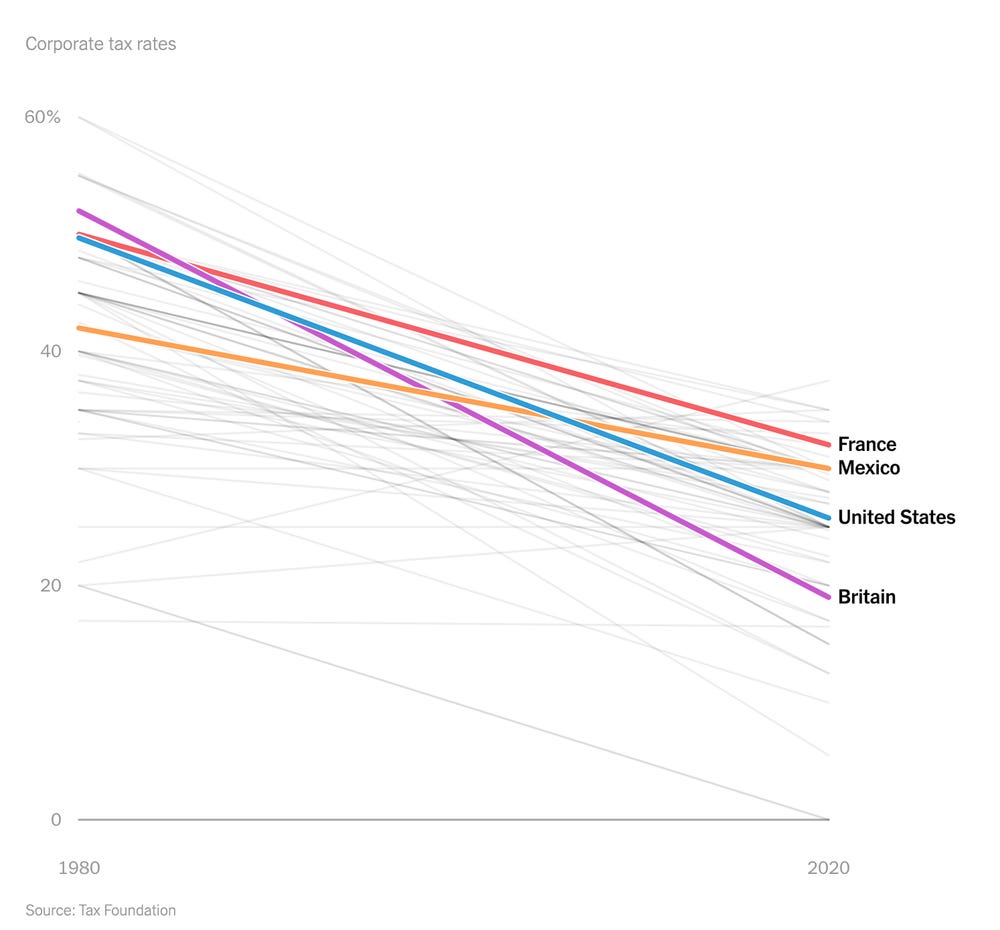

It is chiefly for this reason that tax rates have fallen so precipitously around the world over the past 40 years. But to the frustration of tax offices everywhere, so long as your tax rate isn't the lowest, it pays for companies to hide their profits somewhere else.

Luckily, the solution to this is well established, switching to a destination basis. A destination basis would tax the profits of goods at the location of their sale, removing the capacity for such methods.

In practice, this would entail a reversal of how imports and exports are treated. Rather than taxing exports and leaving imports tax-free, a destination-based tax applies to imports and leaves exports tax-free. This process already occurs with Value Added taxes, and despite what it may look like, the tax on imports is not a tariff.

Under a tariff regime, imports are taxed more heavily than domestically created and consumed goods. Border adjustment, on the other hand, distinctly puts both on a level playing field by taxing the profits derived from both at the same rate.

A cashflow tax utilizing the destination basis, or is it often termed a DBCFT, would finally allow countries to tax capital without fear of avoidance and, crucially, without fear of losing business competitiveness.

2. What are its political prospects?

In the midst of the drafting of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, many congressional Republicans rallied around the idea of a destination-based cash flow tax as a replacement for current corporate taxes. A funny continuation of the tendency of republicans to accidentally propose progressive ideas, like when then-Speaker Paul Ryan proposed a social security reform plan that would actually lead to the socialization of a huge chunk of the capital stock.

It's important to mention that this proposal was a bit different than what an ideal cash flow tax may be like. For starters, it had a rate of only 20%. A rate this low is rather unjustifiable when you consider that the tax hits an economic rent, i.e., something that can be taxed with little negative economic consequence.

Further, their proposal allows losses to be deducted and carried forward with interest instead of being directly subsidized.

If their proposal had been well designed, it would also have included the capability for businesses to sell these deductions to each other. This would be particularly important for exporters, who, as mentioned in a previous section, would never be subject to tax and thus would never have a use for these deductions.

So, instead of the donut shop we mentioned earlier getting paid 10,000 dollars, the sum would be able to be carried forward at the risk-free rate of interest and then redeemed towards future profits. If this interest rate was 2%, in the following year, the government would only receive 29,800 dollars as compared to the 40,000 dollars it would have received if it had directly subsidized the loss instead of allowing it to be deducted.

In either case, the government is effectively subsidizing losses. The only difference is by directly subsidizing them, the government does not lose out on the risk-free rate of return.

For political purposes, this deduction structure may be an essential concession. The notion that the government would be depositing money in the accounts of many businesses each year is surely off-putting to many Americans, but it is necessary to realize that the deduction route doesn't do all that much but deprive the government of some revenue.

Returning to the present, the cash flow tax is fortunate to have a feature that should make it appealing to both sides. It is extremely efficient, especially compared to current corporate taxes, and also somewhat more progressive.

It provides Democrats the prospect of indulging the desire to raise taxes on the ultra-rich without the negative effects that usually come with such policy shifts. And given the fact that Republicans so recently proposed it, it would be quite strange for them to attempt to fearmonger about a policy many of them so recently voiced support for.

3. Won't taxing businesses reduce growth?

Taxing capital is usually undesirable because it distorts incentives. Current corporate taxes reduce investment by directly taxing it; the capital gains tax has a similar effect. Furthermore, in both cases, losses are not made fully deductible, so the risk is not reduced in equal measure to the reward. From this, we get lower investment, lower growth, and thus lower incomes.

The same cannot be said for DBCFT, where revenue is derived not from confiscation but by a partnership. Risk and reward are decreased in equal measure. The interaction is mutually beneficial, the risk of doing business is diminished, and in exchange, the government gets a chunk of the returns that it could never generate through its comparatively less efficient ventures.

4. How much revenue would it raise?

In 2021, pre-tax corporate profits were around 3.4 trillion dollars. When we subtract out aggregate corporate losses and inflation, we can expect to see a smaller sum, but even then, the remaining base of revenue is quite sizable. Furthermore, LLC profits are not included in this figure but would be included under a cash flow tax, and so too would be profits that are currently not accounted for due to the aforementioned "profit shifting practice."

With all that being said, even if we were to assume the base was to be halved in size, a 50% tax would still raise 850 billion dollars annually, making it far larger than present corporate taxes.

5. What will the transitional effects be?

Switching to a DBCFT is a major change, and with it comes major ramifications. First, the DBCFT would act like a 1-time windfall tax on preexisting business assets. This is because all currently existing capital never benefited from the new subsidy but is subject to the new, higher tax.

While that might sound a bit frightening, it is of no concern. Preexisting capital is already in existence; the profit it derives can be taxed at whatever rate with no effect (so long as it doesn't make people wary of investing in the future). What really matters is how taxes apply to new investments.

In terms of wealth distribution, this transitional element is a feature, not a bug. Cutting down on the fortunes of society's richest without negative economic consequences is a huge win, and make no mistake, they are the ones that will bear the brunt of the blow.

To a lesser extent, pensioners will also be hit, but transitional arrangements can be made so as to cushion this blow to the point where it feels like more of a light tap for all but the rich elderly.

Second, because of the switch from origin to destination-based taxation, we will see a big swing in exchange rates. The following excerpt from the WEF describes what occurs succinctly:

“Assuming that corporate tax is 20%, it can be shown that following the alternation of the tax base from exports to imports, the local currency would strengthen by 20%.

Thus, the exporters would lose 20% but will not pay 20% tax as before. Their net income would remain unchanged, and the importers would gain 20% from the local currency appreciation, which will be offset by the 20% tax they now can't deduct – leaving their net expenditure just the same as before the reform.

The only change will be in the exchange rate. All real variables, such as the size of imports, exports, and tax revenue, will remain unchanged.”

This exchange rate change won't be a problem in the long run but will be a jarring shift at first.

In closing, cash flow taxation is an idea whose time has come. In a world of high deficits, persistent poverty, and growing inequality, they are a way to bolster public finances without sacrificing efficiency or progressivity. If it's truly the desire of politicians to improve the lot of the people, a DBCFT is a fantastic place to start.

So let me get this straight. We subsidize business expenses and the tax the returns. Is that it? If so, it's a lot less complicated than I thought.